International Roma Day is devoted to the celebration, expression, and promotion of Romani history, culture, and language. In 1971, during the first World Romani Congress held in London, April 8th was declared the International Roma Day with the establishment of the Roma flag and anthem. At the fourth World Romani Congress in Warsaw the day was officially recognized. To Roma communities the day represents the celebration and expression of Romani history and culture, as well as a day of solidarity among Roma. Further, International Roma Day places an opportunity to highlight the historical and current prejudice Roma face and voice the need for societies to take action to protect the rights of Roma and achieve inclusion in their societies.

Educational systems, the national curricula, and textbook have the responsibility to promote and preserve the Romani history and culture. Additionally, Romani cultural representation within education is critical to mutual understanding of the multicultural identities of European nations, as well as crucial in the pursuit to decreased prejudice and conflict between Roma and the dominant society.

Textbooks influence the creation of stereotypes and intergroup bias

Textbooks have an important role in how social and cultural groups and intergroup relations are perceived. Research shows that individuals develop social categories at a young age. This results in psychological and social meaning, and the assigning of group memberships that create the divide between ‘us’ and ‘them’.[1] The further development of intergroup cognition and conflict comes from interaction with cultural objects and discourses.[2] Textbooks, as cultural objects, represent the larger society and interconnected cultural groups within the social identity, they directly have influence in social discourse about cultural groups[3].

The research shows that the two main factors for intergroup conflict are ‘in-group preference and status-based enculturation’.[4] Status based enculturation in the context of textbook representation of Roma includes how the teaching of groups withing society (Roma and non-Roma) can assign social status valuations based on the group and the internalization of social status based on groups. For instance, how the educational system presents Roma culture and people through stereotypes (unclean, low skilled, criminals) or prejudice which then assigns Roma a lower social status and internalizes high social status in non-Roma. This directly creates intergroup distance and conflict.[5] In other words how the dominant majority enculturation does or does not include ingroup preferences and outgroup devaluation.

Intergroup attitudes shift during adolescents as individuals develop a deeper set of egalitarian and moral values.[6] Racial stereotypes and messaging whether explicit or implicit can reinforce racial resentment which also influence political and social views, even when the individual or society practice hold norms related to equality. [7] When students reach upper primary and secondary school, it is important that textbooks representation of Roma provide lessons that teach and formulate values of morality, justice, and anti-discrimination. This practice can mitigate any intergroup attitudes developed in the early years of the child’s development. Therefore, when representing Roma as a national minority group, there must be honest representation of past and current prejudice framed in evaluations of those prejudices that focus on themes of justice and anti-discrimination.

How is Roma rights and culture represented in school curricula and textbooks

Within Europe and across the globe Romani history and culture is by and large unknown. A recent research report by Roma Education Fund, Georg Eckert Institute, and Council of Europe analyzed the representation of Roma in European curricula and textbooks (find the full report here). The project evaluated the representation of Roma in national curricula, as well as the currently used history, social science, and geography textbooks.

Six main results of Roma culture representation in textbooks[8]

- The Roma culture has an inadequate presence in European textbooks. When Roma people and culture are mentioned, it is in the form of short paragraphs or in side boxes that provide a definition when Roma is mentioned in another context. The practice of explaining who Roma are when mentioned in a textbook is a clear indication that the material is not meant for a Romani reader, but for non-Roma to read about Roma.

- The recognition of April 8th as International Roma Day is only represented in one country’s textbook (Finland). The Roma anthem Gelem Gelem is found only in Croatia, Finland, and Hungary.

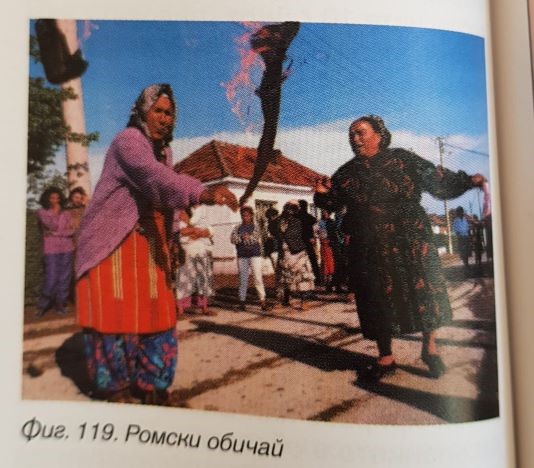

- A number of textbooks present Roma people and culture with stereotypical framing. The stereotypical representation within textbooks are typically present in Central and South Eastern European countries with relatively high proportion of Roma population.

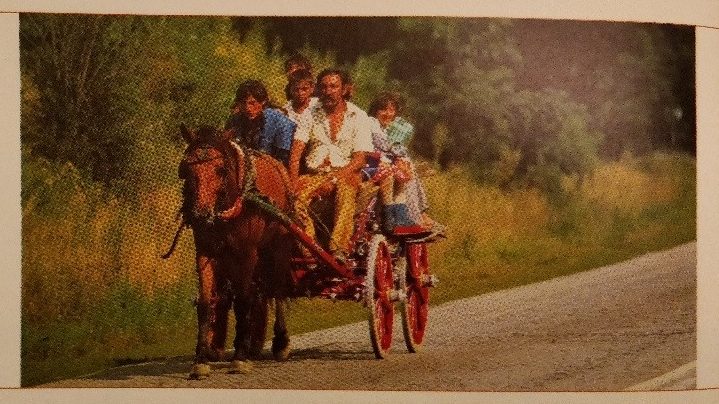

- Textbooks represent Roma culture and people as anachronistic and outdated. Thus, donating a clashing between Roma culture with the dominant society.

- Roma contribution to national or European cultures and societies are almost non-existent.

- Outside of Roma being mentioned as victims of the National Socialist regime, Roma are typically mentioned in their population number and percentage or as a list of national minorities without any additional information on Roma people and their culture.

The images found in textbooks are powerful in their influence to creating and reinforcing stereotypes and prejudice against Roma communities.

There are multiple descriptions of Roma culture as nomadic and other descriptions which are have little grounding in reality in the various Roma cultures.

When discussing children and minority rights there are numerous depictions of Roma children through a lens of culture of poverty. This is specifically present in Albanian textbooks.

Through images textbooks misrepresent Roma culture in ways that create social distance and lack of social understanding between Roma and non-Roma.

Mentions place social status and value to Roma people and culture. Most of this is done through text constructing discourses around ‘culture of poverty’, ‘low skills’, ‘poor education’, and other social valuations.

Five main results of how textbooks present current Roma prejudice and the countering Roma discrimination[9]

- Description of current prejudice and discrimination of Roma is rare. Most depictions are of past persecution during World War II.

- There a few textbooks which connect past persecution to current prejudices, while promoting values of anti-discrimination. Although this is quite rare.

- Mentions which include Roma voices of empowerment and solidarity in their fight for equal rights in current societies are present, although sporadic.

- There are frequent attempts at countering Roma discrimination which reinforce stereotypes and create distance between Roma and dominant society.

- Critically reflecting on the derogatory terms of ‘Gypsy’, Zigeuner’, ‘Tsigane’ or Cigany’ are presented in a limited number of textbooks from Germany and Hungary.

Ways forward

It is important to have strong pedagogy tools to assist in instilling lessons that counter stereotypes as children generally remember stereotypical descriptions better than counter stereotypical description of people with a different race or ethnicity then their own. [10] There some practices that have been successful in reducing prejudice and intergroup conflict which can be translated into textbook lessons which include; categorizing and prioritizing goals and identities outside of race or group affiliations, training regulation of negative emotions, fostering empathy across groups, and real or imagined contact between groups.[11] When presenting Roma people and their culture, textbooks can place values on goals and identities which have high value to both Roma and non-Roma cultures. When portraying Roma people, textbooks must ensure that the content has no possibility of evoking negative emotions. The mentions of Roma can foster empathy and create a sense of contact across groups through using Roma individual voices which provide information on Romani culture, experiences of exclusion and discrimination, all while translating the emotion of the speaker through the text.

International Roma day has placed Roma culture and rights on the international social discourse. Educational systems and textbooks have not caught up with their representation that Roma people and their culture are equally appreciated and valued in society. The textbooks must represent Roma culture and people in the frame of equality, justice, and antidiscrimination to instill these values, as well as challenge and mitigate any prejudice ideology in their societies. We also have to understand that this effort is not a rapid fix. It will take generations of work to shift the social cognition of societies and address intergroup conflict through cultural representation. We, as Roma, must stay resilient and remain proud. Our allies in turn must stay supportive and vocal. Baxtalo Mashkarthemutno Romano Dives.

[1] Ziv, Talee, and Mahzarin R. Banaji. “Representations of social groups in the early years of life.” The SAGE handbook of social cognition (2012): 372-389.

[2]Ibid

[3] Weninger, Csilla, and J. Patrick Williams. “Cultural representations of minorities in Hungarian textbooks.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 13.2 (2005): 159-180

[4] Dunham, Yarrow, Eva E. Chen, and Mahzarin R. Banaji. “Two signatures of implicit intergroup attitudes: Developmental invariance and early enculturation.” Psychological science 24.6 (2013): 860-868.

[5] Weinreich, Peter. “‘Enculturation’, not ‘acculturation’: Conceptualising and assessing identity processes in migrant communities.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 33.2 (2009): 124-139.

[6] Dunham, Yarrow, Eva E. Chen, and Mahzarin R. Banaji. “Two signatures of implicit intergroup attitudes: Developmental invariance and early enculturation.” Psychological science 24.6 (2013): 860-868.

[7] Wetts, Rachel, and Robb Willer. “Who Is Called by the Dog Whistle? Experimental Evidence That Racial Resentment and Political Ideology Condition Responses to Racially Encoded Messages.” Socius 5 (2019): 2378023119866268.

[8] Council of Europe, “The Representation of Roma in European Curricula and Textbooks”, a joint report commissioned by the Council of Europe to the Georg Eckert Institute for International Textbook Research in partnership with the Roma Education Fund 2020. https://repository.gei.de/handle/11428/306

[9] Council of Europe, “The Representation of Roma in European Curricula and Textbooks”, a joint report commissioned by the Council of Europe to the Georg Eckert Institute for International Textbook Research in partnership with the Roma Education Fund 2020. https://repository.gei.de/handle/11428/306

[10] Bigler, R.S., & Liben, L.S. (1993). A cognitive-developmental approach to racial stereotyping and reconstructive memory in Euro-American children. Child Development, 64,

[11] Cikara, Mina, Emile G. Bruneau, and Rebecca R. Saxe. “Us and them: Intergroup failures of empathy.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 20.3 (2011): 149-153.